I have 45 minutes to write this.

If I don’t do it by then, I’ll chicken out and go back outside for another smoke.

There’s this memory that keeps playing in my head that I’ve tried to suppress many times, but the more I try to block it out, the slower it gets. My dad is sitting next to me in the car. He’s yelling, not quite at me because his eyes are on the road and the bottle in his hand. I couldn’t even get his attention when he was mad at me.

I’m 4 years old. I don’t know yet that the clear liquid in the bottle he’s drinking from is gin. I think it’s water. My dad drives the car magically; his hands aren’t on the steering wheel. One hand holds the bottle, the other hand rests outside the window, a cigarette between his fingers.

He just keeps yelling. Louder and louder. I’m crying. Louder and louder. My sandalled feet dangle off the leather seat.

Cigarette ash swirls around inside the car like the snow I won’t see for another 20 years. The wind kicks up. It’s both a blessing and a slap in the face in the dry San Antonio, Texas heat. My short hair is stuck flat to my head from a combination of tears and sweat.

He just keeps yelling. The consonants and vowels that spew out of his mouth have formed this amorphous blob that pulsates between us. The shape gets bigger and bigger until it’s burst by a siren’s blare.

Then it’s like someone hits the fast forward button, and we turn the corner, fast, to my abuela’s neighborhood. I had a hard time pronouncing “abuela” as a kid, so it came out more like “uela.”

She was already standing guard in the doorway, wearing her flowered mumu and slippers.

The car screeches to a halt and my dad slams his door open and makes a run for it up the lawn. I look into the rearview mirror and see the cop do the same. My abuela is yelling something in Spanish.

I slowly open the passenger door and walk up the driveway. I try not to look at my dad. He yells my nickname, “Jordie,” out of breath, and I can’t help but look at him. We lock eyes as he struggles on the ground.

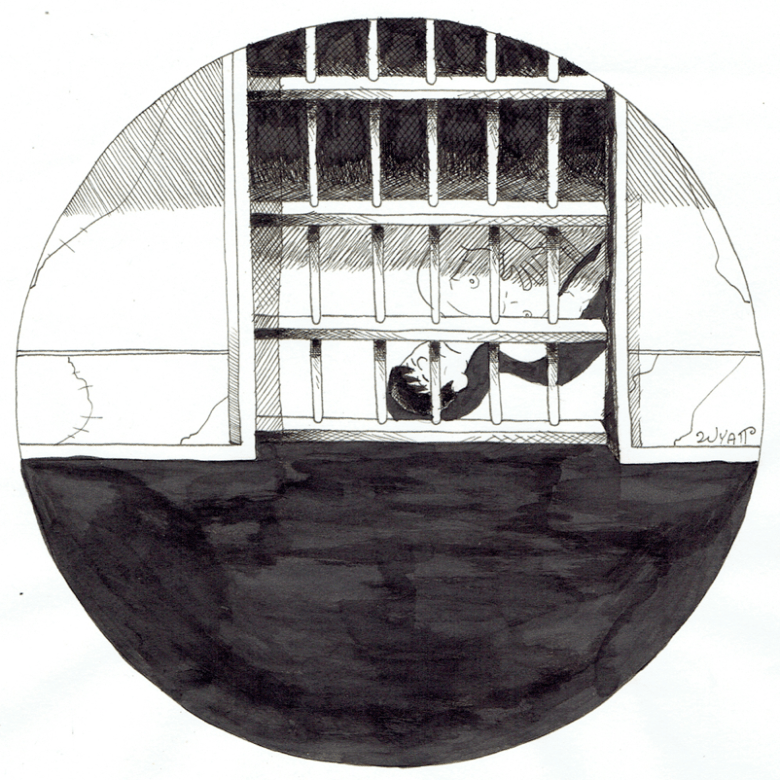

The cop is mouthing something, but I don’t hear him, just see his lips move and his arms get tangled in my dad’s as he clicks the handcuffs on. It feels like they stayed on that lawn for hours before my dad was dragged backwards toward the cop car.

There’s one tree in my abuela’s lawn. Its arms cast a dark shadow, trying to grab my dad and pull him into the house. My abuela keeps yelling, but this time it’s in English. She’s asking me over and over: “What did you do?”

Today, at 31 years old, I still can’t answer that question. It haunts me like Casper, the ghost movie my dad was supposed to take me to see that day. This was supposed to be our time together. He had promised me he would take me to see the movie at Rolling Oaks Mall, just us two. But there we were on the lawn.

Did I do something to get my dad arrested? Was my abuela too lenient with my dad as a kid? Why did my dad as a kid pick up my grandfather from the bar?

We had started our day at a pizza place, where we met up with a woman and her daughter. My dad told me to go play while he drank beer. Then we went to the mall, only we didn’t make it past the parking lot. We weren’t going to the movie theater like he had promised we would. This news brought me to tears. I couldn’t stop crying. He. Had. Promised. I was getting louder and louder. He grabbed my arm and told me we were leaving. Years later, when I was in middle school, I began to wonder: Was his arrest my fault? Did a cop see me crying and think my dad was kidnapping me? Is that why the cop followed us?

I did eventually see Casper, when it came out on VHS. I’m not sure if it was worth the wait, but now that movie is synonymous with one of my earliest memories. It’s one of the triggers that can bring the day of his arrest flooding back.

Walking past a police precinct: Could my dad be in that cop car that just pulled up?

Listening to any sort of ’80s New Wave music: My dad’s favorite band was Spandau Ballet.

Watching Law & Order: In my mind, there goes my dad, handcuffed in the back of a cop car.

I wish my abuela was still alive so I could tell her these things. She died when I was 14, never knowing the extent of my anger towards her. It’s not just anger, it’s also pity. I pity her: She saw my dad get arrested more than once. She bailed him out. She gave him money. He stole money from her. All of this, and she still blamed me.

Blame. That’s something Law & Order and other police dramas don’t talk about. The blame that’s placed on the families or family members of people who are incarcerated. The blame we placed on one another. Did I do something to get my dad arrested? Was my abuela too lenient with my dad as a kid? Why did my dad as a kid pick up my grandfather from the bar?

There are gritty crime dramas that explore life in prison, like Oz and Prison Break. There are heartfelt dramas about people being wrongly accused and released from prison, like The Hurricane. And then, maybe the worst of the bunch, there are prison comedies that make life on the inside look like a sorority house. (I’m talking to you, Orange Is The New Black.)

Most of these prison shows find closure with the main character being reunited with their loved one.

My reality has been a lot different. The last time I saw my dad I was around 8 years old. I don’t remember anything from this meeting, except that it happened somewhere outside of a prison. In hindsight, this was to be expected; my dad moved around a lot, and eventually left the U.S. for Spain, where his maternal family is from. I don’t think this move abroad was because he wanted to connect with his familial roots. I’m pretty certain it was to evade arrest. The last time I searched my dad’s name in a background check he still had an outstanding warrant for his arrest in the U.S.

There are more than 5.2 million people who have had a parent incarcerated at some point during their lives. I’m one of those people, my mom’s one of those people, and my half-sister’s one of those people.

My stomach hurts thinking about my dad’s experiences in prisons throughout his life. When I was in high school, my stomach hurt so bad I had to be taken out of school for a semester and taught from home. I was prescribed Xanax for my anxiety, an ailment that’s plagued me since elementary school and continues to cause me to miss work. Kids of incarcerated parents are nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with anxiety, according to research from the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University.

To help combat these feelings, I’m open with friends and colleagues about my dad’s rap sheet. Their response is usually something pretty heinous, like: “Wow, you turned out so well,” or, “And you even went to grad school.” Sometimes they ask me questions: “Did you ever visit your dad in jail/prison? Write him letters?” No, no I did not, I tell them. That was a choice I made. This isn’t the movies. Not every kid who has a parent who’s incarcerated wants to communicate with them.

Sometimes I feel like I’d rather host a seance and try to communicate with my dead abuela than find out where my dad is in the world. I know I’ll never have closure. And closure’s one of those things that movies and TV shows about the criminal (in)justice system love to portray.

Closure can come in many forms, but for movies and TV, it’s usually in the form of an in-person visit to the prison by a family member. This person sits there in front of the plexiglass divider, speaking into a handset across from their loved one in the orange jumpsuit. Sometimes there is no divider, and hugs and kisses can be exchanged.

There was an episode of The Sopranos like this, and it got to me. One of the mobsters is in a prison hospital, dying from lung cancer, when his wife and daughters come to visit him. He’s carrying his oxygen tank and pissing his wife off by smoking a cigarette. I sometimes thought this was what visiting my dad in prison was going to be like; it would have to take him dying for me to go visit him.

The movie White Oleander also struck a nerve with me. The main character infrequently visits her mom in prison, and they exchange handwritten letters. My dad never wrote me a letter, at least not one I know about, and that still hurts me in the way that a paper cut stings; it seems harmless, and there’s usually little-to-no blood, but there’s a lot of nerve endings on fingertips.

Prison movies sometimes have that shot of a loved one and the person who is incarcerated pressing their palms together between the plexiglass. I always thought that was disgusting and hoped they both washed their hands after.

I must have held my dad’s hand at some point. Our palms must have touched. I don’t remember what that felt like if we did. I do remember my dad’s hands clasped together behind his back when the cop dragged him off the lawn.

This is why I call it the (in)justice system: There was no justice the day my dad was arrested. A cop threw my dad face down on his own mother’s lawn in front of his child. My dad’s arrest didn’t help him find treatment for his substance use disorder. It also didn’t mean my mom would receive child support payments.

I’m never going to be reunited with my dad. My eyes are all stingy right now. Typing that was hard. Are my 45 minutes up yet?

I’ve written a movie treatment where the main character, not unlike myself, sees her estranged dad around New York City. In the end, spoiler, he’s a ghost. He’s dead. He died. My dad might be dead. And I can’t even thank him for my expensive cigarette habit and preference for gin.

This doesn’t stop me from searching his name in databases and on social media. I have a Google Alert set for him. The only piece of information I’ve found in the past decade is an article written in an outlet based in Lima, Peru, about my dad getting arrested there for trafficking cocaine from Spain into the city. He spent seven years in a Lima prison. My mom called me one night to tell me she’d watched an episode of the TV show The World’s Toughest Prisons where they featured a prison in Peru. We still wonder if that was the location where he was held.

I talked to my mom recently about the event and we debated whether my dad had called my abuela before we left. This was 1995. I don’t remember my dad having a bag phone at the time, even though my mom said he did. This would explain why my abuela was waiting for us in the doorway. I always just thought she had heard the sirens and assumed they were coming her way; she was used to cops showing up at her house, partly because of my dad.

There are more than 5.2 million people who have had a parent incarcerated at some point during their lives. I’m one of those people, my mom’s one of those people, and my half-sister’s one of those people.

My abuela always sided with her sons. It was never their fault. My dad’s arrest happened because of a bratty 4-year-old. That kid, me, still feels that blame. Grandmothers are supposed to love and protect their grandchildren. Fathers are supposed to at least pay child support. My grandmother and father are exceptions to the rule.

I can’t remember what I told my abuela; there was a lot of crying and yelling. But I remember I asked my mom if my abuela would have believed me if I was a boy. She said maybe, but I probably would have still been yelled at. The day my dad was arrested, my mom drove more than an hour to pick me up. I only remember her being angry at my abuela and threatening to keep me away from my grandmother. What I would tell her now is that at 4 years old, I maybe had seen my dad a handful of times. He was a stranger to me. Why would I have wanted this stranger to get in trouble? I also knew how much my abuela loved my dad; she had framed photos of him around her house. Why would I have wanted to hurt her?

Over the next decade, my brain would be filled with happy memories of my abuela, and a few indifferent memories of my dad. There’s images of me and my abuela feeding the birds pieces of bolillos, dressing up to go to that same mall where my dad didn’t take me to see Casper, and hanging out at her friend’s house, the one that made the beaded socks.

These memories stacked on top of one another, trying to suffocate the smell of tobacco and leather and the sounds of sirens. But the day my dad was arrested, that memory would squirm through the cracks to the top, always happening at the most inconvenient time.

Other times, I’m awash with anxiety. There are different ways my anxiety has physically manifested itself throughout my life. I used to bite my nails and the skin around them so bad that pustules would form, marking the places where I had bitten. My mom would dip a safety pin in rubbing alcohol and pop them. I still bite my nails, just not that bad. Later, I would pick at my hairline. It’s still difficult for me to look at some of the photos taken during that time because there’s a bald spot.

I used to cry in front of the mirror. One of my aunts had a hallway of mirrors leading to the guest bathroom. After she found me standing there crying a few times she would walk with me to the bathroom. It became a family joke.

I often joke about all of these experiences I’ve spent the past 44 minutes writing about. Laughing means I’m not crying. Not looking into a mirror too long means I won’t cry.

But I think it’s time I see my dad in my face: the almond-shaped hazel eyes, the thick, bushy eyebrows. I no longer try to fight back tears. I just don’t go to therapy anymore.

My time is up. I’m going out for a smoke.