Constitutional Limitations & Options for Preventing Abuse

Executive Summary

As president, Donald Trump claimed that Article II of the U.S. Constitution provided him with “the right to do whatever I want.” This view of unfettered presidential powers extended to the pardon power, which Trump similarly claimed was unconstrained. “[T]he U.S. President has the complete power to pardon,” Trump asserted during his first year in office. Later, he would claim that this included an “absolute right” to pardon himself.

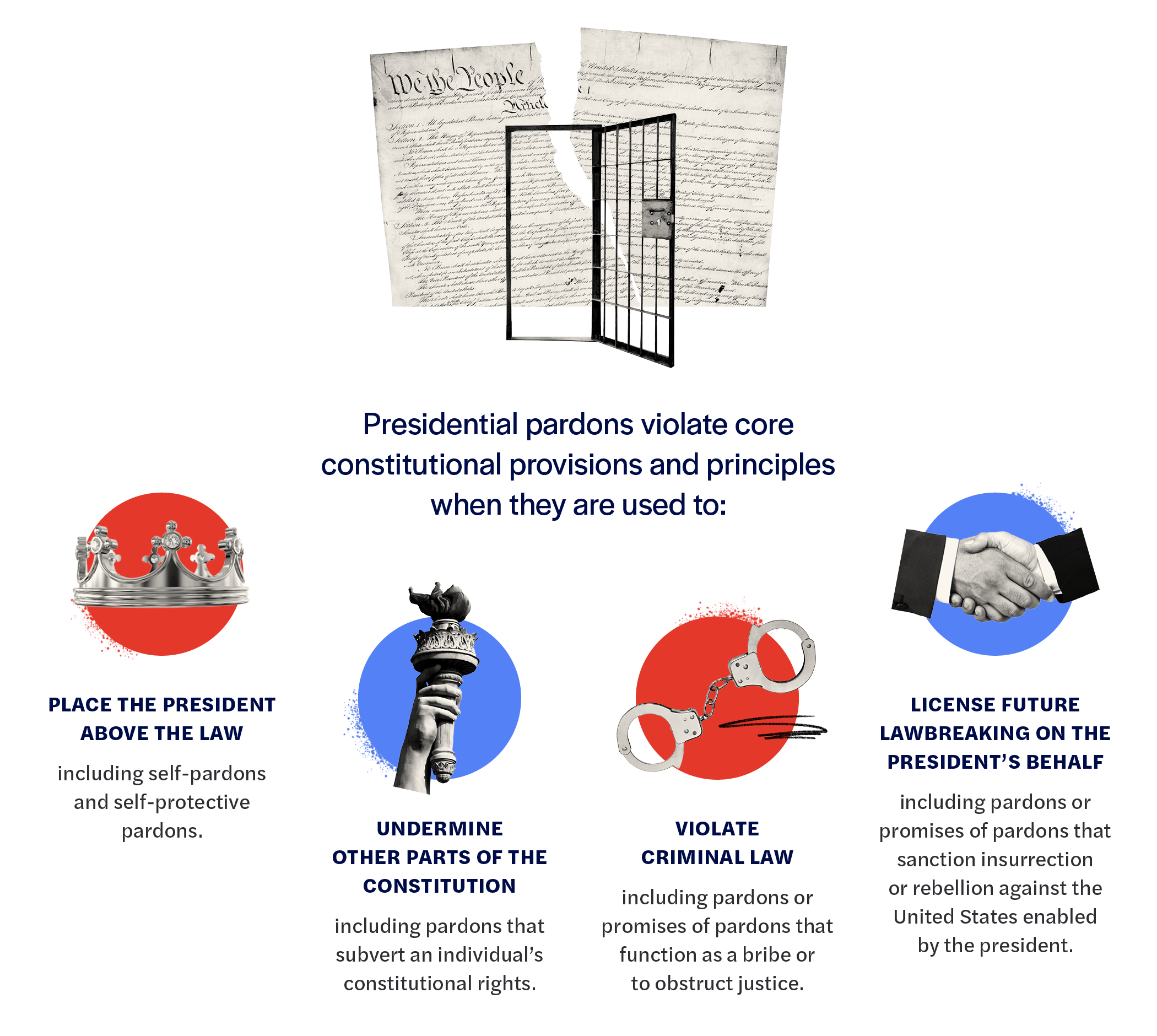

Trump is not alone in his view of a president’s unlimited power to pardon. Various commentators have echoed the former president’s claims. This paper reviews what are, to the contrary, an array of limitations. Various types of pardons violate core constitutional provisions and principles, including those used to:

- Place the president above the law;

- Undermine other parts of the Constitution, including constitutional rights;

- Violate criminal law; or

- License future lawbreaking on the president’s behalf.

Each branch of government has constitutional tools at its disposal to prevent and respond to the pardon power’s abuse. This paper reviews certain options.

The president is not a king, and all powers vested with the office of the presidency are subject to the Constitution’s system of checks and balances. The pardon power is no exception. This paper is intended to be a resource for understanding the specific limitations the Constitution places on the pardon power as well as certain constitutional tools available to fortify them.

When Pardons Breach Constitutional Limits

The president is not a king, and all powers vested with the president are subject to a variety of constitutional limitations. The pardon power is no exception.

Introduction

Presidents enjoy an expansive constitutional power to grant clemency for federal crimes. Article II (Section 2, Clause 1) provides that the president “shall have the Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.”

In 2017, former President Donald Trump claimed that this power was “complete.” The claim echoed similar assertions made by prior administrations. In 1919, dismissing a congressional request for pardon papers, President Woodrow Wilson’s Attorney General claimed that the “President, in his action on pardon cases, is not subject to the control or supervision of anyone, nor is he accountable in any way to any branch of the government for his action.” President Dwight Eisenhower’s pardon attorney reaffirmed the position: “In the exercise of the pardoning power, the President is amenable only to the dictates of his own conscience.” President Bill Clinton was advised that any cooperation with congressional oversight of his pardon power would be entirely voluntary.

Yet each branch of the federal government in fact can—and does—check the president’s pardon power. Federal courts may adjudicate disputes over the constitutionality of a pardon, as they have since the early 19th century. In Burdick v. United States, for instance, the Supreme Court held that a president may not pardon someone against his will. Congress may also investigate, impeach, and remove a president from office for abuse of the pardon power. In its articles of impeachment against President Richard Nixon, the U.S. House cited his efforts to obstruct justice by dangling pardons to potential Watergate witnesses. The executive branch itself may investigate criminal abuses surrounding the exercise of the power. In 2001, federal prosecutors empaneled a grand jury after a pardon by President Clinton that appeared to be a quid pro quo with a donor in potential violation of federal bribery law.

Each branch performs these checks because the power to pardon is not, in fact, absolute under our Constitution. Several constitutional limitations curtail a president’s authority to grant pardons. This paper reviews abuses of the pardon power—when the exercise of the power breaches constitutional limitations—and the roles each branch of government can and should play to exercise constitutional checks. In its review of abuses, it explains how various categories of pardons would violate certain constitutional provisions and principles, posing threats to the rule of law. In particular, it explains why, consistent with our constitutional framework, presidents cannot:

- Grant self-protective pardons, or those that would have the intent and effect of impeding an investigation into themselves or their interests, amounting to a self-pardon;

- Use pardons to subvert individual liberties protected by the Bill of Rights;

- Use pardons to prevent courts from enforcing orders to protect those rights;

- Grant or propose to grant pardons (e.g., “dangled pardons”) that violate generally applicable criminal laws, such as those that would obstruct justice or constitute bribery; and

- Grant or propose to grant pardons that run afoul of their constitutional duty to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed,” such as those that license lawbreaking on their behalf.

In certain circumstances, the constitutional limits of the pardon power have been tested and litigated, and courts have articulated clear guidance. For instance, it is settled law that presidents may not grant a pardon for a crime that has not yet been committed. In others, potential uses of the power—for instance, to attempt to grant a pardon to oneself, or to grant pardons that evidently sanction and encourage lawbreaking on a president’s behalf—are untried. But just because a certain exercise of the pardon power is untested, or that its exercise has not yet been reviewed by a court, does not imply it is permissible under our Constitution. As presidents increasingly push the power into untested terrain, each branch of government must be especially watchful and willing to check abuses. Not just judges, but also members of Congress and executive branch attorneys, take oaths to uphold the Constitution and have obligations to do so. Those obligations apply to checking abuses of the pardon power that run afoul of the Constitution.

According to one legal scholar, since the Watergate era, “Presidents have been more willing to use clemency not merely as an ‘act of grace,’ or ‘for the public welfare,’ as the framers intended, but also as a political weapon to close investigations of their allies or to reward political contributors.” As with many abuses of executive power, however, Trump supercharged the self-dealing use of the pardon power. As a Washington Post investigation of all clemency acts during his tenure concluded: “Never before had a president used his constitutional clemency powers to free or forgive so many people who could be useful to his future political efforts.” This included a record number of pardons for white-collar criminals who would go on to provide political and financial support to the former president.

Should Trump win the presidency in 2024, he will almost certainly attempt to again wield the power in even more abusive ways to place himself, his co-conspirators, and other loyalists beyond the reach of the criminal justice system. Today, the former president is now a criminal defendant in multiple state and federal jurisdictions. He faces 44 charges in two federal criminal cases and another 47 charges between two other state criminal cases. Various close associates are also now under state and federal indictment.

At various times throughout his presidency, relying on the logic of a supposed unconstrained pardon power, Trump considered a self-pardon to broadly insulate himself from potential future prosecutions, and also considered a range of preemptive pardons for family members and close associates. As Trump broadcasts his intentions regarding how he would again use the pardon power—a power that Alexander Hamilton observed should “inspire scrupulousness and caution”—this paper offers a framework for assessing whether those uses comport with the president’s obligation to faithfully uphold the Constitution and the laws of the United States.

Executive clemency powers are not unfettered. The Pardon Clause is no different from others in the Constitution that assign particular powers to a branch of the federal government, all of which must accommodate one another. As the Supreme Court has held, the Constitution grants the president the “power to commute sentences on conditions which do not in themselves offend the Constitution.” The pardon power, like all others, must be understood within the structure of the Constitution as a whole. Each branch of government in turn has a critical constitutional role to play in checking its abuses.

Source link